I never planned to become immersed in eating disorder research. It started with a friend’s recovery journey, then snowballed into years of conversations with survivors, treatment professionals, and those still struggling. What shocked me most wasn’t the statistics, but the vibrant online subculture that keeps these deadly disorders thriving. So here’s my messy, imperfect attempt to share what I’ve learned about everything from the toxic wasteland of pro-ana twitter to the surprising power of eating disorder prayer.

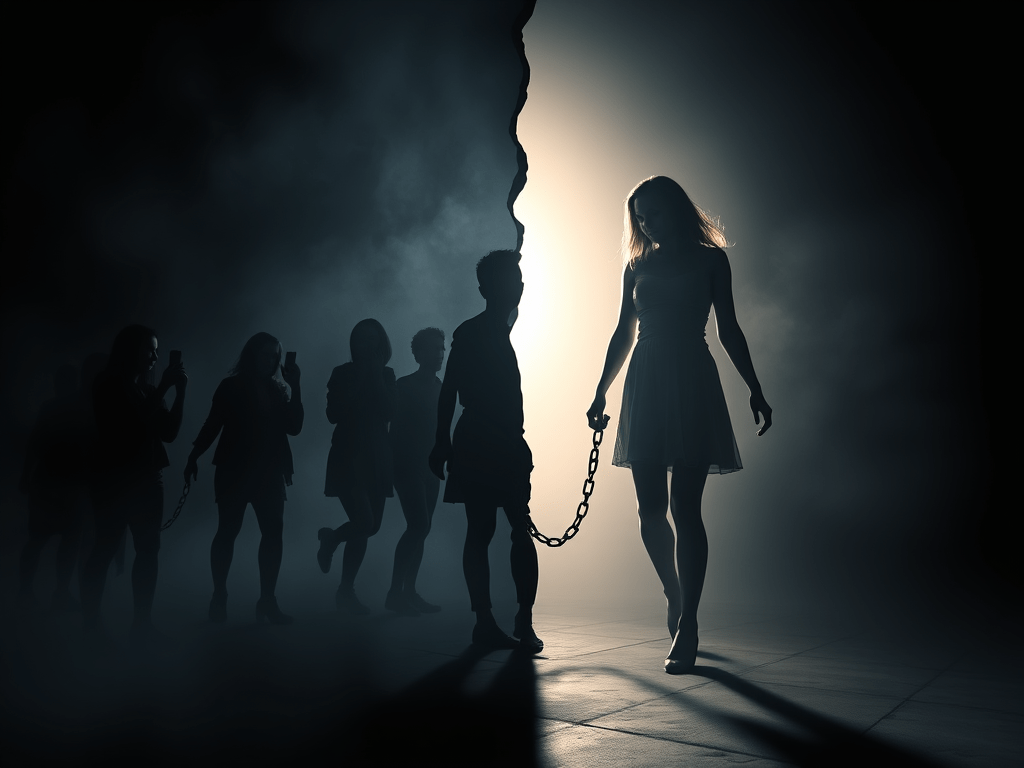

Pro-Ana Twitter and Meanspo Tumblr: The Digital Danger Zone

God, pro-ana twitter terrifies me. The first time I stumbled across it while researching for a friend in treatment, I felt physically ill. These weren’t just people discussing their disorders—they were actively coaching others into self-destruction through coded language that platform moderators couldn’t easily detect.

One recovered woman I spoke with (let’s call her Jenna) told me: “I followed over 50 pro-ana accounts. They taught me every trick—how to hide weight loss from parents, how to make it look like you’ve eaten when you haven’t, even how to lie to doctors about symptoms. I was 15 and thought these people were my friends.”

Then there’s meanspo tumblr, which might be even worse. “Meanspo” is shorthand for “mean inspiration”—essentially, users request and receive verbal abuse to discourage them from eating. The messages are brutal: they call users fat, disgusting, worthless. They tell them no one will love them until they lose weight. And here’s the twisted part—people deliberately seek this abuse out.

A 22-year-old I interviewed (who asked to remain anonymous) said something that still haunts me: “During my worst period, I had meanspo notifications set to ping my phone before meals. I needed that voice telling me I was a fat pig who didn’t deserve food. It sounds insane now, but back then, it felt like motivation.”

And don’t even get me started on the anorexia tumblr quotes that made starvation seem poetic. These weren’t just text—they were artfully designed images with phrases like “Collarbones are the new diamonds” or “Skip dinner, wake up thinner” in dreamy fonts over black and white photos. They made a deadly mental illness look aspirational, turning self-destruction into something beautiful and meaningful.

REVOLUTIONARY WEIGHT LOSS BREAKTHROUGH!🔥 Unlock your body’s natural fat-burning potential with a secret celebrities have been hiding! 💪

Anorexia and Bulimia Combined: When Disorders Get Complicated

One question I get all the time when people learn about my research: can you have both anorexia and bulimia? The short answer is absolutely yes, and it’s incredibly common. The neat categories in psychology textbooks rarely match the messy reality of actual eating disorders.

Take my friend Rachel (name changed). Her experience with anorexia and bulimia combined was a rollercoaster that traditional treatment protocols weren’t designed to handle. “I’d restrict heavily for weeks, then inevitably crack and binge, then panic and purge, then restrict even more severely as punishment,” she told me over coffee last year. “My dietitian finally said something that clicked: ‘Your body is fighting for survival on multiple fronts.’”

What many people don’t realize is that restriction often triggers binging—it’s a biological survival response. When the body is starved, it will eventually override mental control and drive a person to eat, often far beyond comfortable fullness. The shame that follows can trigger purging behaviors, and then the cycle continues. This isn’t a failure of willpower; it’s biology.

The medical term “anorexia nervosa binge-eating/purging type” acknowledges this overlap, but in my experience, many healthcare providers still approach treatment as though eating disorders exist in neat, separate boxes. Meanwhile, people suffer in the messy middle, feeling like they’re “failing” at both restricting and recovery.

Is Starving Yourself Haram? When Faith and Eating Disorders Collide

“Is starving yourself haram?” A Muslim college student asked me this during a campus panel discussion last year. The vulnerability in her voice broke my heart—I could tell this question had been tormenting her. Religious guilt had become tangled with her eating disorder, creating a complicated knot of shame and confusion.

I’m not a religious scholar, but I’ve spoken with several while researching the intersection of faith and eating disorders. Most religious traditions—including Islam—emphasize caring for the body as a divine gift or trust. Sheikh Ahmad (who counsels Muslim youth with mental health struggles) explained it to me this way: “In Islam, your body is an amanah—a sacred trust from Allah. Deliberately harming it contradicts our principles of self-care and moderation.”

Christians struggling with eating disorders often find meaningful support in bible verses about eating disorders—or more accurately, verses about the body, nourishment, and freedom that they apply to their recovery journey. A treatment center chaplain shared that 1 Corinthians 6:19-20 (“your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit”) helps many patients reframe their relationship with food as an act of stewardship rather than control.

One of the most moving interviews I conducted was with a woman who developed an eating disorder prayer practice during her recovery. Maria, now ten years into recovery, shared this with me: “I couldn’t talk to anyone about what I was going through, even my therapist sometimes. But I could talk to God about the terror I felt around food. Prayer became the one place where I didn’t have to pretend or perform.”

Her daily prayer began: “God, help me see my body through your eyes today, not through the eyes of this illness or this broken culture.” Simple, but powerful.

Eating Disorders and Thanksgiving: A Holiday Survival Guide

Eating disorders and Thanksgiving—talk about a horrific combination. While everyone else celebrates food and togetherness, people with eating disorders are white-knuckling through what feels like a gauntlet of terror.

Last November, I sat with four women in recovery as they prepared for the holiday. Their anxiety was palpable as they shared their fears: relatives commenting on their bodies or eating habits, the expectation to eat large portions in front of others, diet talk around the table, and the hours of food-centered interaction with nowhere to escape.

“My aunt always watches what I eat,” said one woman, fidgeting with her sleeve. “Last year she said, ‘I’m so glad you’re eating normally again,’ and I had a panic attack in the bathroom afterward. She thought she was being supportive, but it felt like a spotlight on my every bite.”

Their treatment center had given them practical strategies: identifying a support person who would be present, planning specific responses to triggering comments, scheduling a check-in call with their therapist, and having an exit plan if things became overwhelming.

One woman’s strategy particularly stuck with me. “I bring a small object in my pocket—this year it’s a smooth stone with the word ‘breathe’ carved into it. When I start to feel overwhelmed, I hold it and it reminds me that this is just one meal on one day, not a definition of my recovery.”

Fasting After Binge Eating: The Terrible Advice That Makes Everything Worse

Can we please talk about how much terrible advice circulates about eating disorders? The worst I’ve encountered is the widespread belief that fasting after binge eating will “reset” your system or “balance out” the calories.

This advice is everywhere—from fitness influencers to well-meaning friends—and it’s absolute poison for anyone with disordered eating patterns. Breaking this cycle was the hardest part of my friend Sam’s recovery from binge eating disorder.

“Everyone—including my doctor at the time—told me to ‘get back on track’ after a binge by eating super clean the next day,” Sam told me during a long walk last fall. “No one explained that restriction was what triggered my binges in the first place. I spent seven years in that hellish cycle before a specialized dietitian finally explained that consistent, adequate nourishment was the only way out.”

The cycle works like this: Restriction leads to physical and psychological deprivation, which eventually triggers binging, which triggers shame, which leads to more restriction as an attempt to “fix” the perceived mistake, and around it goes. The only way to break this cycle is to step off the restriction merry-go-round—something that feels terrifying when you’re caught in disordered patterns.

I’ve seen the profound relief on people’s faces when a qualified professional finally gives them permission to eat normally after a binge instead of punishing themselves with more restriction. It feels counterintuitive, even wrong at first. But consistency is what ultimately heals the biological and psychological drivers of the binge-restrict cycle.

The Winter Weight Panic You Don’t See Coming

There’s something particularly insidious about winter thinspo—that specific category of “thinspiration” content designed to motivate weight loss during colder months when bodies are typically covered by more clothing.

I first noticed this trend three winters ago when researching seasonal patterns in eating disorder behaviors. While mainstream diet culture has its January resolution frenzy, eating disorder communities have their own darker version that starts circulating in late autumn.

The content typically features captions like “No hiding in winter clothes” or “What will you look like when coat season ends?” alongside images of extremely thin people in winter clothing. The messaging creates constant vigilance and fear—even when the body is covered, there’s no relief from the pressure to shrink.

A college sophomore shared her experience with me last February: “Winter used to be my safe time. I could wear sweaters and feel less exposed. Then I found all these winter thinspo blogs talking about how winter was actually the most important time to lose weight. Suddenly my one season of less intense body anxiety was ruined too.”

This seasonal approach makes disordered eating seem normal and cyclical rather than the serious mental health condition it is. It mimics mainstream diet culture’s seasonal messaging but takes it to dangerous extremes.

How to Stop Head Hunger: Beyond Physical Hunger

Learning how to stop head hunger was the turning point in my friend Ellie’s recovery from compulsive eating. “Physical hunger was never my problem,” she told me over tea last spring. “I rarely felt it. What drove my eating was this constant mental preoccupation with food—thoughts, urges, fixations that had nothing to do with my body’s actual needs.”

Head hunger (sometimes called “mental hunger” or “emotional hunger”) is that psychological urge to eat that’s disconnected from physical need. It might be triggered by emotions, habits, boredom, or simply the sight or thought of food. And it’s incredibly common, both in eating disorders and in our food-obsessed culture generally.

What fascinated me in my conversations with specialists was how they approached this issue not as something to overcome through willpower, but as signals to be decoded. “Head hunger always contains information,” explained one eating disorder dietitian I interviewed. “The goal isn’t to fight it but to get curious about what it’s telling you.”

Ellie’s breakthrough came when she started using what her therapist called the “pause practice”—taking 90 seconds when she felt the urge to eat to check in with her body and emotions. “I wasn’t trying to talk myself out of eating,” she explained. “I was just creating space to understand what was driving the urge. Sometimes it was legitimate hunger I’d been ignoring. Sometimes it was anxiety or loneliness. Sometimes it was just habit. Understanding the difference changed everything.”

ARFID: The Eating Disorder Nobody Understands

The question “is ARFID a disability?” landed in my inbox after I wrote a newspaper article about lesser-known eating disorders. The person asking had been struggling to get workplace accommodations for their condition. Their employer’s response? “Being a picky eater isn’t a disability.”

That response shows the profound misunderstanding surrounding Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). Unlike anorexia or bulimia, ARFID doesn’t involve body image distress or fear of weight gain. Instead, it involves severe food restrictions based on sensory sensitivities, fear of negative consequences (like choking), or lack of interest in eating.

One mother I interviewed had a 14-year-old son with severe ARFID who could only eat about seven foods. “People think we’re indulging a picky eater,” she said, frustration evident in her voice. “They don’t see the terror in his eyes when faced with new foods, or understand that he would literally starve rather than eat something his brain has categorized as unsafe. He’s been hospitalized three times for malnutrition.”

In legal terms, severe ARFID absolutely can qualify as a disability under the Americans with Disabilities Act and similar laws in other countries. It meets the definition when it substantially limits major life activities—which can include eating, concentrating, working, or even socializing when food is involved.

The disability recognition isn’t just about legal protection—it’s about acknowledging the very real limitations the condition imposes. A college student with ARFID shared: “Having ARFID recognized as a disability meant I could access meal plan exemptions and have flexible attendance policies for classes scheduled during my supported eating times with my therapist. Without those accommodations, I would have had to leave school.”

Anorexia Nervosa Recovery Stories: The Truth That Gives Me Hope

I’ve interviewed dozens of people with anorexia nervosa recovery stories, and they never fail to move me. These aren’t just before-and-after tales—they’re complex narratives of reclaiming life from a disorder that has one of the highest mortality rates of any mental illness.

Maya’s story particularly stays with me. I met her at a conference where she was speaking about her ten-year recovery journey. Over coffee afterward, she shared something I’ll never forget: “Recovery wasn’t just about gaining weight or normalizing my eating. It was about discovering who I was beyond the illness. For years, ‘anorexic’ was my primary identity. Finding out who Maya actually was—her interests, values, dreams—that was the real recovery work.”

What I find most powerful in these recovery narratives isn’t the physical transformation but the mental freedom described. People talk about the realization that they can go to restaurants without checking the menu in advance, travel without packing safe foods, attend social events without anxiety, and experience emotions without using food behaviors to cope.

“I didn’t believe full recovery existed,” one woman told me five years into her stable recovery. “My previous treatment team had told me I’d always struggle to some degree. Finding recovered people who were truly free around food gave me something to fight for.”

These stories matter tremendously. When you’re in the depths of an eating disorder, recovery can seem impossible. Hearing from people who have made that journey provides concrete evidence that healing is possible, even from the most entrenched disorders.

ABC Diet Before After: The Dangerous Deception No One Should Try

I hesitate to even discuss the ABC diet before after phenomenon because I worry about accidentally providing a roadmap to self-destruction. But the misinformation surrounding this dangerous protocol needs addressing.

The “Ana Boot Camp” diet is a 50-day starvation regimen that circulates in eating disorder communities. It prescribes calories ranging from 0-800 daily in a pattern supposedly designed to “trick the metabolism.” The “before and after” images shared in these communities show dramatic weight loss while deliberately hiding the catastrophic health consequences.

I spoke with an emergency room doctor who has treated multiple patients who attempted this diet. “What the ‘after’ photos don’t show is the heart damage, bone loss, and organ dysfunction,” he told me, visibly frustrated. “I had a 19-year-old patient whose heart rate had dropped to 38 beats per minute following this protocol. She nearly died for a before-and-after photo.”

The reality these images conceal includes:

- Dangerous heart conditions

- Hormonal disruptions affecting everything from mood to fertility

- Bone density loss that may never fully recover

- Cognitive impacts including difficulty concentrating

- Emotional effects including depression and anxiety

A former patient shared: “The ‘after’ picture everyone praised was taken three days before I was hospitalized with heart complications. I spent my 20th birthday in the cardiac unit. Six years later, I’m still working with specialists to address the damage.”

What makes this diet particularly insidious is its pseudo-scientific presentation. The specific calorie counts and pattern give the impression of a legitimate protocol rather than what it actually is—a roadmap to self-destruction.

When You Can’t Trust Your Own Mind

One theme that emerged repeatedly in my conversations was the profound distrust of oneself that eating disorders create. People described not being able to trust their hunger, fullness, food choices, or even their own thoughts about their bodies.

“My eating disorder lied to me constantly,” explained one woman six years into recovery. “It would tell me I was huge when I was dangerously underweight. It would tell me I’d binged when I’d eaten a normal meal. It would tell me everyone was staring at me with disgust when they were actually concerned for my health.”

This distortion of reality is one reason why eating disorders are so difficult to overcome without support. When you can’t trust your own perceptions, you need external reality checks from professionals and trusted support people.

One recovery tool I’ve seen work powerfully is what some therapists call “eating disorder thought records”—structured ways to document distorted thoughts and challenge them with reality-based responses. Over time, this practice helps rebuild trust in one’s own perceptions and judgments.

A woman three years into recovery from bulimia shared her experience: “I still sometimes have the thought ‘I’ve ruined everything’ after eating a fear food. But now I can recognize that as my eating disorder voice, not my authentic self. I can respond with what I know is true: ‘One meal doesn’t define my worth or my recovery.’”

This ability to distinguish between the eating disorder’s voice and one’s authentic self represents a crucial milestone in recovery—one that often requires professional guidance to achieve.

Finding Your Way Forward

If there’s one thing I’ve learned through years of conversations about eating disorders, it’s that recovery isn’t about willpower or motivation—it’s about access to proper treatment, support, and hope. The path looks different for everyone, but certain elements seem universal: proper nutrition rehabilitation, psychological support to address the underlying issues, and community to replace the isolation that eating disorders create.

Whether you’re personally struggling, supporting someone who is, or simply trying to understand these complex conditions better, I hope this messy collection of what I’ve learned offers some insight or direction. These disorders thrive in silence and isolation—honest conversation is one powerful antidote.

Recovery is hard, complex work. But I’ve seen too many people find their way through to believe it’s impossible for anyone. As one recovered individual told me, “The eating disorder promised me safety, control, and worthiness, but delivered isolation, fear, and physical deterioration. Recovery was terrifying, but it gave me everything the disorder falsely promised and more.”

WANT TO BURN STUBBORN BELLY FAT FAST? 🔥Here’s your ultimate tool! Just stir this tasteless powder into your morning coffee and see the magic unfold! 💪

Leave a comment